By reflecting our blind spots back to us, AI can potentially guide us in how to design with awareness rather than habit.

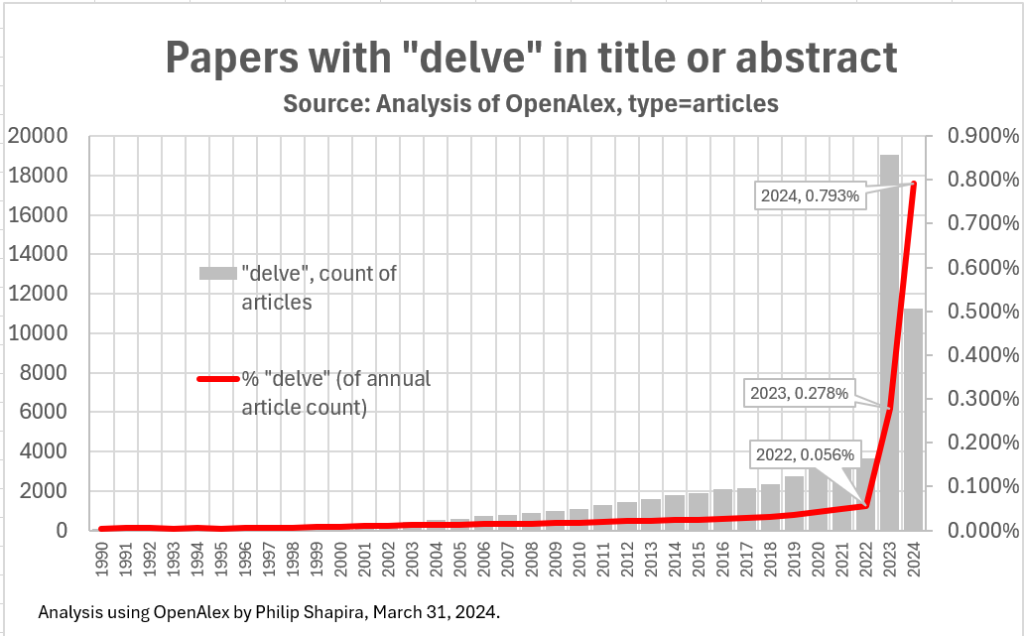

From the 15th century to the early 21st century, the usage of the word "delve" remained relatively consistent and at a very low frequency.

Then something mysterious happened sometime toward the end of 2022 and the beginning of 2023: a dramatic and unprecedented increase in the word's frequency, particularly in scientific writing and academic abstracts.

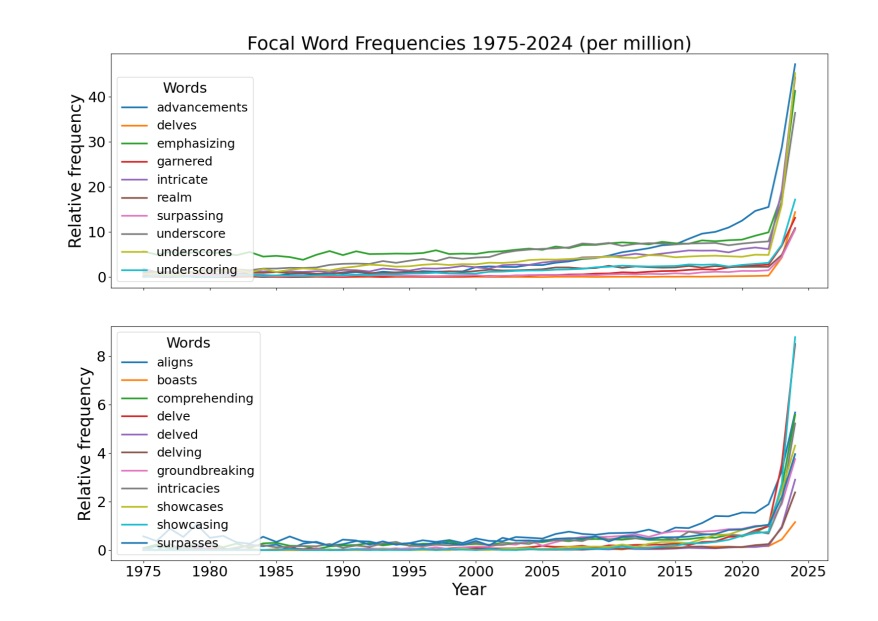

Interestingly, words like “innovative”, “notable”, “pivotal”, and “intricate” show a similar, sudden higher frequency starting from around the same time. The launch of ChatGPT in November 2022 is not purely coincidental here.

Curious about this sudden linguistic anomaly, researchers at Florida State University set out to answer a strangely simple question: Why does ChatGPT “delve” so much? To investigate, the team compared thousands of scientific abstracts from 2020 and 2024, looking for words that had suddenly spiked in popularity.

Then they asked ChatGPT to rewrite the 2020 abstracts and compared the results. Strikingly, many of the very same words, for instance, “delve,” were also the ones ChatGPT was overusing in its own versions. They also found that the model wasn’t inventing a language on its own. Instead, Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) played a crucial role.

This means it’s not just raw internet text that shapes AI’s language habits. Rather, the human judgments we feed into the system are actively teaching the models to overuse certain words. And when we consistently reward certain words (“this sounds good, this sounds professional”), the model learns to overuse them.

And when human beings are increasingly exposed to AI-generated texts, these AI-preferred words become more mainstream through repetition and a feedback loop. So, words like “garner”, “meticulous”, and “delve” are making inroads into everyday conversations.

This is where the story gets interesting: if AI can stealthily reshape our word choices, what else might it be reinforcing and amplifying? So the biases built into our language, culture, and even design don’t passively sit in the background, but they get pulled into a feedback loop between humans and machines, becoming more powerful, pronounced, and visible.

Which leads to the central question of this post: can biased AI become the mirror we need not only to reflect our blind spots back at us, but to help us design with more self-awareness and intention?

Where bias comes from and how it gets into AI

According to cognitive neuroscientists, humans are conscious of only about 5% of their cognitive activity. Most of what we call decision-making happens below the surface of our awareness. As much as we like to think we choose our words while we speak or write, we simply pick them from a hidden library, the arrangement of which is shaped by our habits, culture, and social expectations, and the language we are exposed to. Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel laureate psychologist, called this our “System 1”, which is fast, intuitive, and uncritical.

That mental shortcut wouldn’t be a problem unless it was full of biased or sexist and otherwise problematic language we pick from day-to-day conversations, cultural shorthand, the books we read, and the movies we watch. Look at this line from the classic “To Kill a Mockingbird”:

“I swear, Scout, sometimes you act so much like a girl it's mortifying.”

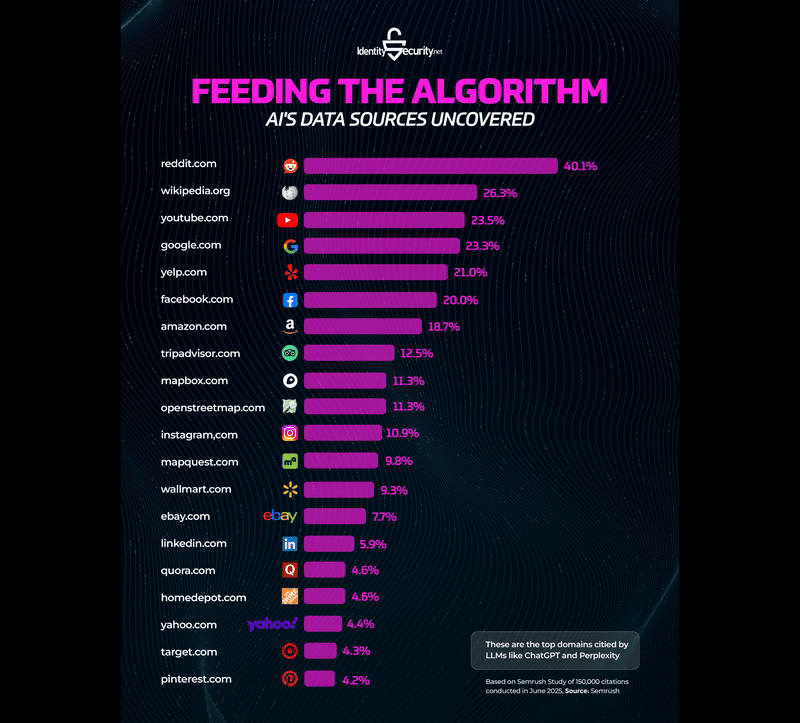

Now route all this into AI’s learning process. Large Language Models (LLMs) are trained on a huge swath of text that comes from everywhere, starting from classics and the Bible to Reddit threads and TripAdvisor reviews.

LLMs don’t invent a fresh dictionary; they simply feed on ours. They learn the patterns baked into their training data, and if those patterns favor one type of language framing over another, the model reproduces them. In fact, it often does so more fluently and with more authority than a human writer. This makes the bias look even more natural, and it’s where the problem gets trickier.

Humans tend to trust machines (probably more than we should). Psychologists call it automation bias: it’s the habit of agreeing to a system simply because the outputs look more polished, objective, or authoritative. Studies across medical decision-support tools to everyday apps show the same pattern: people often accept automated suggestions without much scrutiny. We then carry those machine-led biases forward in our real lives.

Here’s how this complete human-AI loop reinforces bias:

Unconscious human bias creeps into training data → this data shapes AI outputs → humans treat those outputs as sacrosanct and rely on the output → human adoption leads to reinforced bias.

Slowly, we might stop noticing how much of our communication is guided by inherited patterns. So, if you are using “delve” or “evolving” a little more frequently, you know where the nudge is coming from.

Insights from cognitive linguistics

Language does much more than describe things; rather, it often triggers actions and even shapes our perception of reality. According to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, also known as the principle of linguistic relativity, the words we speak influence our thoughts and perceptions.

For instance, people who speak different languages may perceive colors, time, or emotions just slightly differently because their linguistic categories nudge them differently. British researchers found that color words shape perception: English-speaking kids with a Crayola 64-pack can tell “rust” from “brick” or “moss” from “sage,” while kids from languages with fewer color terms lump them together.

According to the Speech Act Theory, language is used to perform actions beyond just conveying information. So, when I say "I apologize," I'm not describing an apology; I’m actually performing one. Similarly, conceptual metaphors, for example, calling employees “rockstars” vs. “team players”, convey different images of roles, power, hierarchy, and individualism.

It’s not rare to see that impact in hiring. In a classic 2011 study titled “Evidence That Gendered Wording in Job Advertisements Exists and Sustains Gender Inequality” by Gaucher, Friesen, and Kay showed that the language used in job advertisements can affect who applies for a position.

Masculine-coded words in ads like “competitive,” “dominant,” or “leader” made jobs less appealing to women, while feminine-coded words like “supportive”, “interpersonal”, “collaborative”, and “cooperative” had a similar effect on men.

If gender-coded job ads can influence real people’s decisions in measurable ways, imagine what happens when LLMs, trained on an enormous dataset of human writing, inherit those same word associations. AI models no longer use “competitive” or “supportive” as neutral descriptors of job roles; they amplify the cultural baggage and overtones attached to them.

Consequently, when recruiters or candidates rely on AI-generated descriptions, those subtle nudges start scaling and amplifying. Even tiny linguistic biases that once shaped a single job ad now have the power to influence thousands of postings at once, with the polish and authority of machine-generated text. Welcome to the new era of machine-generated texts.

But the story doesn’t need to end there.

AI as a bias detector

If AI can reinforce those sneaky old biases, it can also shine a floodlight on them. The same mirror that throws our blind spots back at us can be designed to catch us in the act!

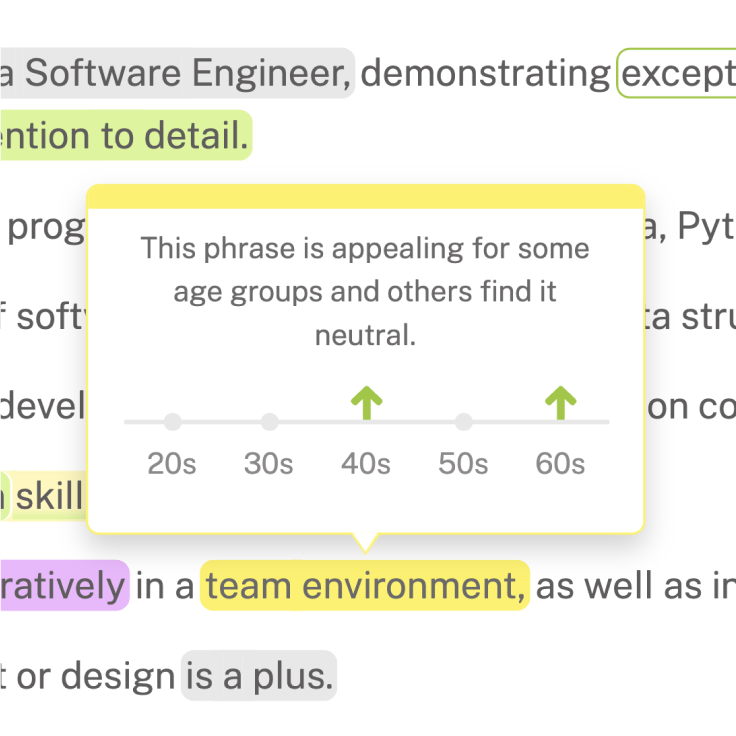

Let’s take the example of Textio, an AI-powered hiring tool. It uses AI to correct unconscious bias. So, when you type biased terms like “rockstar developer” or “driven leader,” the platform signals, Hey, did you know this language historically attracts mostly men?

Textio picks these patterns from a massive dataset of real job postings, hiring outcomes, and applicant pools. It has seen, at scale, how certain words tilt the playing field, and it turns that invisible skew into something visible right on your screen.

Instead of handing you a ready-made rewrite, the tool forces you to pause and rethink your own choices, making you aware of the implications of your language choices. Over time, that builds a different kind of muscle memory: words that we choose consciously rather than lazily pulling them from our cultural shorthand.

Companies that have leaned into this approach are attracting measurably more diverse and qualified candidates. T-Mobile, for instance, attracted 17% more female candidates using Textio.

Yes, AI amplifies human biases we are often unaware of. On the negative side, this means AI can pick subtle cultural assumptions or exclusionary phrasing and project them at scale, and turn our hidden bias into systemic patterns to influence thousands of decisions. On the positive side, we can design the same systems in ways that expose those biases and problematic areas to guide us toward more conscious choices.

The Textio example shows that AI doesn’t have to be the lazy autopilot that reinforces the same biases that characterize our language and cultural shorthand. We can use AI as a smart copilot to surface our blind spots and ask whether the words we’re leaning on are the ones we actually want to use. When designed this way, AI stops being a passive amplifier and becomes a smart partner we can actively learn from.

The big question is whether we’ll use that mirror to replace thinking or to think better.

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow us on LinkedIn