When creating digital products, especially those designed for people with disabilities, it’s important to keep key principles of inclusion and accessibility in mind. These concepts apply to all stages of product development: from ideation and creation to GTM and marketing.

General principles

Social vs. medical models of disability

There are two primary approaches to understanding disability: the medical model and the social model.

The medical model frames disability as a deviation from the so-called “norm”, where physical or mental disabilities are viewed as issues within the individual. The goal in this model is often treatment or rehabilitation to bring the person closer to what is considered the “norm.”

The social model, on the other hand, sees disability as one of many human characteristics. Disability is seen as resulting from the way environments and societies are structured. Its goal is to reduce or remove environmental barriers and ensure equal opportunities for everyone.

The medical model tends to ignore individual experiences and needs, focusing instead on “fixing” differences. This approach can be limiting when striving to build a more inclusive society and digital environment.

Therefore, it’s better to refer to the social model, where disability is seen as something that arises when an individual interacts with a non-inclusive environment. If we remove those barriers, the disability becomes just one aspect of who a person is, not a limitation.

For example, a deaf person can watch a movie if it has subtitles. A wheelchair user can attend in-person classes if the building has ramps, elevators, and wide doorways. A blind person can order food through an app if it’s screen reader accessible.

Designed with accessibility in mind – convenient for everyone

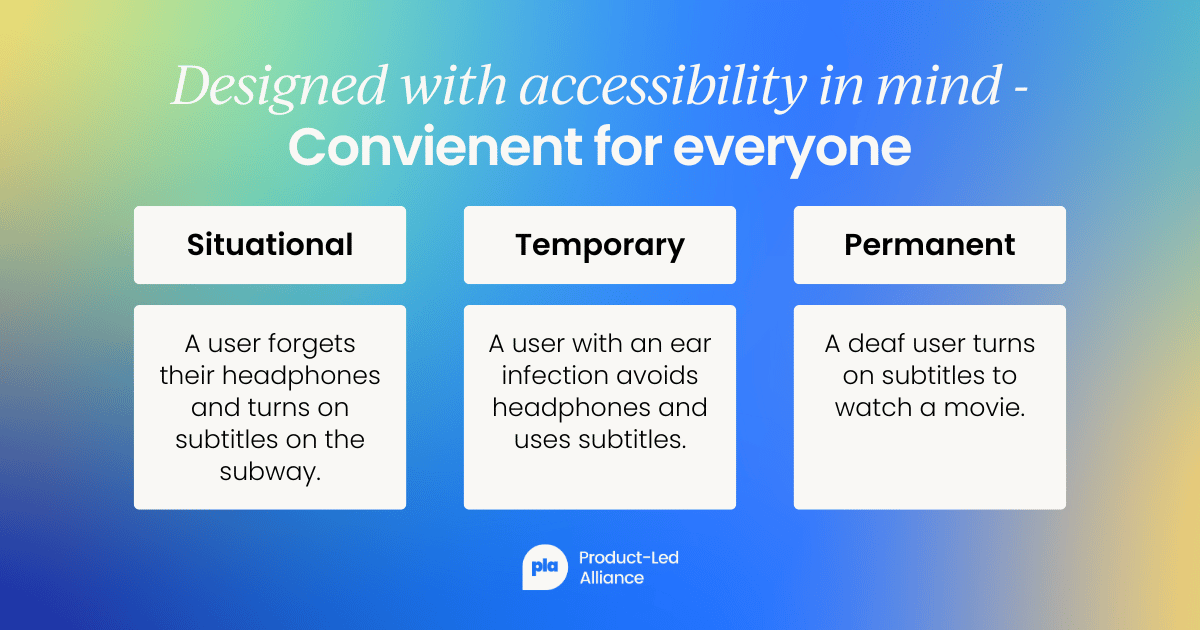

A key principle of inclusive product development is "Designed with accessibility in mind – convenient for everyone."

This principle, introduced by Kat Holmes, former Director of Inclusive Design at Microsoft, stems from the concept of permanent, temporary, and situational disabilities, where accessibility features can benefit all users, not just people with disabilities.

Focusing on the functionality of features and what pain points they can solve is key. What may seem like an accessibility feature often benefits a wider audience.

For example, subtitles for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (SDH) are not just useful for deaf or hard-of-hearing users. They are also helpful for people recovering from an ear infection, watching videos in noisy places like public transport, or browsing content in quiet spaces like libraries.

Nothing about us without us

One of the cornerstones of inclusion is the principle: “Nothing about us without us.”

In product development, this means involving people with disabilities throughout the entire process – from research and discovery to testing. If you don’t have people with disabilities on your team, you can collaborate with non-governmental organizations or associations representing blind, deaf, or mobility-impaired individuals, among others.

This principle also applies to marketing and PR. Messaging and scripts should be reviewed by people with disabilities, and ideally, multiple perspectives should be considered. If you’re creating video content, ensure that characters with disabilities are portrayed by actors with disabilities.

Accessibility, product adaptation, and alternative formats

Creating inclusive products involves three main components:

- Accessibility: Ensuring compatibility with screen readers, scalable fonts, high contrast modes, voice control, keyboard navigation, etc. The primary reference here is the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG).

- Product Adaptation: Adding features that improve usability for people with disabilities. For example, a “Do Not Call” option in a food delivery app can be essential for deaf or hard-of-hearing users.

- Alternative Formats: Adapting content to accommodate various sensory needs—vision, hearing, touch. Consider the following best practices:

- Add text or audio descriptions to images

- Write complex articles in simple, clear language

- Include subtitles and audio descriptions in video content

Once the general principles are in place, it's important to consider the language used when discussing inclusive technologies. The second part of this article outlines key do’s and don’ts to keep in mind.

Language-related principles

Person-first vs. identity-first language

- Person-first: Puts the person before their health condition. For example: “a person who uses a wheelchair”, “a blind person” or “people with disabilities”.

- Identity-first: Emphasizes the disability. For example: “the Deaf,” “the blind.”

While person-first language is generally viewed as more respectful and inclusive, some people prefer identity-first language as their disability is a core part of their identity. It’s best to ask individuals what they prefer.

In professional or corporate contexts, person-first language is typically recommended for its neutrality.

It's important to note that some outdated terms related to people with disabilities are considered offensive within the community. That's why it's crucial to research and validate your language directly with your audience.

Emotionally charged language around disability

Avoid expressions like:

- “Suffering from…”

- “Struggling with…”

- “Overcoming obstacles…”

- “Despite a disability…”

- “Relief from difficulties…”

These phrases imply assumptions about a person’s experience. Not all people with disabilities feel they are suffering or struggling, and many people without disabilities may experience hardship as well.

Instead, use neutral language such as:

- “Has a disability”

- “Lives with a disability”

- “Is a person with a disability”.

People with disabilities vs. so-called “normal/regular” people

Framing people with disabilities in opposition to “normal” or “regular” people reinforces the medical model and suggests there is a default standard everyone should meet. This ignores individual experiences and undermines inclusion.

Phrases like “people with disabilities are just like us (referring to people without disabilities)” or “people with disabilities are the same as everyone else” may aim to convey equality but unintentionally highlight a perceived difference, suggesting people with disabilities are "other." It's better to avoid such comparisons altogether.

Pity and heroization

In marketing, PR materials, social media, or even onboarding content, it's important to avoid two extremes: pity and heroization.

Pity sounds condescending. For example, saying a feature “helps make life a little easier for people with disabilities” might seem like it’s assumed their life is inherently harder. It sounds more like a subjective assessment of what a “hard” or “easy” life might look like, therefore, it’s better to avoid such phrasing and focus on the functionality.

For example, for a ride-hailing app: “this feature allows a user to inform a driver if they use a wheelchair” or for a video streaming app: “subtitles make video content more accessible for diverse audiences, including deaf and hard-of-hearing people”.

Heroization, on the other hand, highlights only extraordinary achievements. For instance, showing a person with a disability only if they’re a Paralympian or head of an association.

A better approach is to show everyday experiences: a blind person watching a movie with audio description, or a wheelchair user ordering a taxi. The goal is to normalize disability and remove stigma by portraying realistic, relatable scenarios.

Conclusion

By integrating inclusive practices into product design, language, and communication, we can begin to reduce environmental barriers and dismantle stereotypes. While this may not solve everything, it’s a meaningful step toward a more inclusive digital experience – and ultimately, a more inclusive society.

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow us on LinkedIn