You’ve almost certainly heard the term “wartime product management” before. It comes up at meetups, in conversations, sometimes in passing – and people tend to nod as if everyone knows exactly what it means.

I’m not sure we always do, and I’m even less sure the comparison is as straightforward as it sounds.

I've got a unique perspective on this. See, I'm on my second career (though I still feel too young to say that). Before diving into the world of product management, I spent over a decade as an army officer. So, when someone first told me about "wartime product management," my immediate thought was: Really? Is it though?

The version of me in the right-hand photo wouldn’t have been impressed by the comparison. He’d have told me to pipe down and get some perspective.

But here's the thing – the more I've lived through the chaos of scaling startups, the more I realize there might be something to this comparison after all.

In this article, I’ll draw on lessons from both worlds – my time in the army and my time leading product teams – to unpack what “wartime” and “peacetime” leadership really look like in practice, and why most organizations spend far longer in between than they expect.

Along the way, we’ll look at:

- What actually defines wartime product leadership, beyond the buzzwords

- How teams can earn credibility, trust, and legitimacy in the stabilization phase

- How to stop depending on a few heroes and instead put simple systems in place so things don’t fall apart

- How the principles of military mission command can be adapted to help product teams weather any storm

Let’s dive in.

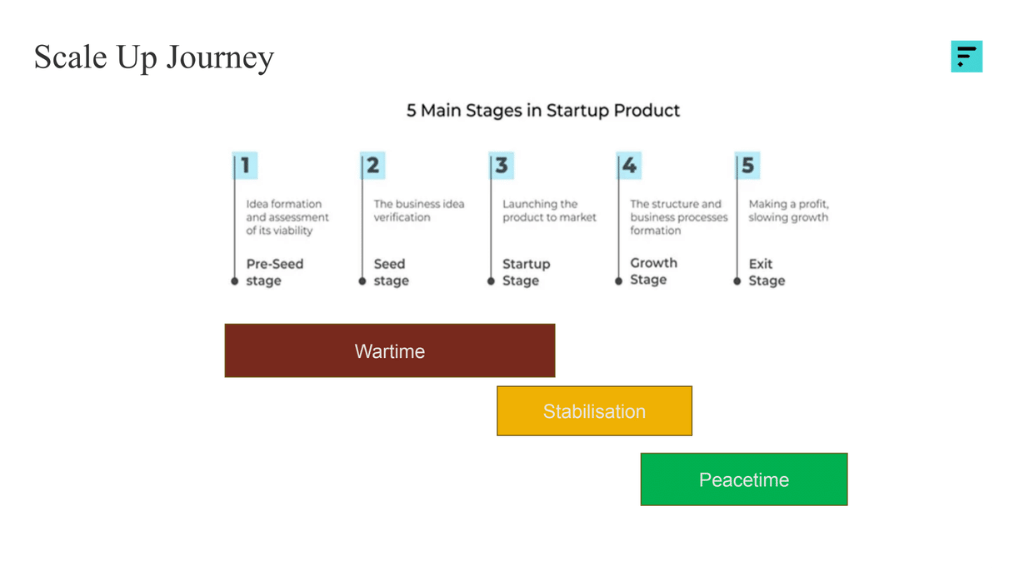

The scale-up journey product leaders are sold

We’ve all seen some version of the diagram. You start as a small, scrappy startup living off seed funding. Then you move up the ladder – VC funding, private equity, and, eventually, a nice, clean exit at the top.

In that story, the early days are framed as “wartime”: chaotic, messy, and intense. After that comes a period of stabilization. Then, finally, peacetime – where things calm down, systems hum along nicely, and life gets a little easier.

Simple, right?

The part that the diagram tends to gloss over is just how long that wartime phase actually lasts. In reality, it takes up a much bigger chunk of your life as a product leader than most people expect.

What wartime product leadership really feels like

In those early startup days, everything feels urgent. You’re constantly reacting, just trying to make it from one day to the next without something critical breaking.

The decisions never stop. They’re fast, they’re high-stakes, and there’s a very real sense that if you get too many of them wrong, the company simply won’t survive. External threats are everywhere, and it’s exhausting.

In that environment, your leadership style has to adapt. You end up being more directive than you might like. You have to make calls with incomplete information, operate within broad intent, and hope your judgment holds up. Above all, you need resilience – quite a lot of it.

If this sounds familiar, that’s because most product leaders have lived some version of it.

For expert advice like this straight to your inbox twice a month, sign up for Pro+ membership.

You'll also get access to 10 certifications, a complimentary Summit ticket, and 100+ tried-and-true templates.

So, what are you waiting for?

A wartime leadership lesson from my first deployment

As I’ve hinted, my first real lesson in what “wartime” feels like didn’t come from a startup – it came from my first operational deployment.

The plan, on paper, was simple. Two teams, two helicopters, landing side by side in the middle of the desert. My colleague was more senior than Ime, so technically I wasn’t even in charge. I remember thinking I’d got an easy ride.

As with most military operations, we’d rehearsed this countless times. You rehearse until it becomes second nature, so that when the pressure hits, you don’t have to think – you just execute.

The helicopters landed. I looked to my left, where the other team should have been.

Nothing.

The helicopters lifted off. Still nothing. We couldn’t reach them on the radio. The whole place felt unnervingly silent.

It was my first time on the ground in that kind of situation, and despite not being the most senior person there, I was responsible for my group. I could feel myself starting to flap.

I went over to my sergeant, who had twenty years’ experience and five or six operational tours behind him, and tried to explain that I couldn’t raise the other team. He leaned back, put his feet up on the handlebars of his quad bike, folded his arms behind his head, and said, “They’ll turn up, won’t they?”

And, of course, they did.

The product parallel

Years later, I found myself in a very different setting, but with a strangely familiar feeling.

In my early days at Flagstone, we were an early-stage startup building a brand-new platform. The existing platform? We largely ignored it. Why fix bugs there when the new platform would solve everything?

The problem was that the new platform was taking far longer than expected. In the meantime, bugs were piling up, and customers were feeling the impact. Eventually, my engineering counterpart and I started campaigning to fix issues in the live system. That meant releasing to production for the first time in around four months.

By the time we committed to it, the pressure was intense. We rehearsed the release repeatedly, ran it through test environments, and built a very detailed runbook. By the third or fourth rehearsal, we felt confident enough to do the real thing in the middle of the night.

The release went perfectly – right up until I logged in to check the system.

I told my engineering counterpart it wasn’t working. He assumed I meant the new feature. I had to clarify: nothing was working. We spent the next hour panicking, trying to work out what had gone wrong, and attempting to roll back – only to discover we couldn’t.

At about 1 a.m., we did what most teams eventually do in moments like that: we called Chao, the engineer who knows everything (every organization has one!). Within about 37 seconds, he identified and fixed the issue.

Wartime doesn’t mean you’re on your own

Both of those experiences taught me the same lesson. When you’re in wartime mode, it can feel like the weight of the world is sitting squarely on your shoulders. You feel responsible. You feel exposed. You feel like you’re supposed to have all the answers.

In reality, there is almost always someone around you with more context, more experience, or deeper knowledge who can help steady things.

Even in the earliest, most chaotic stages of a startup, you’re rarely as alone as you think.

What changes – and what doesn’t – in the stabilization phase

Once you've survived the initial fire of the wartime phase, you move into the stabilization phase.

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow us on LinkedIn